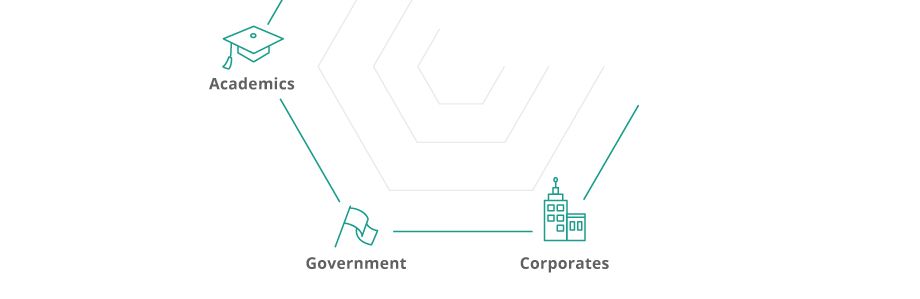

In the 1990s, professors Henry Etzkowitz and Loet Leydesdorff, put forward the idea of the Triple Helix framework, which highlighted academia alongside corporates and government as key pillars of innovation in a knowledge-based society.

The role of universities remains as critical as ever when it comes to fostering an environment that supports and nurtures entrepreneurship. As the Coronavirus pandemic has put many out of work and is proving to be the catalyst for people to start their own business, students who are eager to tackle some of society’s most urgent and present problems, are also increasingly looking to enter the startup world ahead of pursuing traditional employment.

With giants like Google, Tesla and Apple no longer requiring employees to hold university degrees, universities are under pressure to adapt to this changing world and enable an environment of innovation from within.

This then creates an opportunity for universities to extend their support to entrepreneurship beyond academia and instead become agents of economic development by supporting venture creation and commercialising the outcomes of research.

Over the past few years, several universities across the Middle East and North Africa (Mena) have incorporated entrepreneurship and innovation into their curricula in the form of credit courses and degree programmes. Yet as with so much in academia, the focus can often become the grade, rather than truly learning and mastering the skills needed for setting up a successful business.

Others have established inhouse innovation and entrepreneurship centres in a bid to foster entrepreneurship skills while some universities have gone beyond that to establish research hubs, incubators and occasionally venture funds that provide support for the commercialisation of early stage ideas of students, as well as faculty and alumni. They offer activities including bootcamps, mentoring programmes and entrepreneurship resource centres that provide students with networking opportunities with venture capitalists, business angels, established entrepreneurs and mentors.

“Data doesn’t support that education alone is sufficient. There has to be some change in the higher education system,” says Ramesh Jagannathan, research professor of Engineering at NYU Abu Dhabi, vice provost for innovation and entrepreneurship and managing director of entrepreneurship platform startAD. “We teach students that just having an idea does not make you an entrepreneur, but there is a process how to convert that idea into a minimum viable product.”

startAD created systematic incubation programmes for university students and offers a capstone where undergraduate students can participate in one of its programmes and be embedded just like a startup. It gives them curricular credit and real-life learning, in addition to exposure to investors and corporate partners -whose collaborations represent a vital and key success factor for university entrepreneurship support by providing industry know-how and investment.

It is an approach also adopted by Saudi Arabia’s Taqadam, part of the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). Taqadam offers a runway programme for startups looking to commercialise their research, a connection-based programme to follow up with startups post-graduation, in addition to a funnel programme that tests the appetite and talent prior to kick-off.

Taqadam focuses on very early stage startups, knowing these young talents have an idea of how things should be done but they lack expertise of the implementation.

“We connect them with the experts and industry players,” says Arwa Shafi, ventures associate at KAUST and co-leader at Taqadam Entrepreneur University. “We would like to be the ones taking new technologies into the market. We do aspire for students to come up with startup ideas, but we also equip them with skills, resources and connections that we know will leave them there eventually.”

Recent studies found a gap between education for entrepreneurship and knowledge transfer, because in universities, commercialisation of technology occurs in controlled environments and its development beyond this context to commercialise viable innovations to market-fit products is not always supported.

Students and researchers are usually highly interested in working with industrial colleagues. It is the institutional environment that hinders them from doing so more effectively.

“We are supporting a push approach for innovation, where students have ideas and try to find a need for them, in addition to a pull approach, where we bring together industry players with students and startups to create a transdisciplinary team, bringing different perspectives to come up with solutions to actual challenges,” says Nihel Chabrak, CEO at the UAE University’s (UAEU) Science and Innovation Park (SIP).

SIP aims to create a pipeline through competitions to come up with ideas that can be transformed into products they can then bring to market.

Through SIP, UAEU offers startups pilot opportunities in-house where possible. “This is a way for them to go to market in a very friendly environment, and a chance for us to test and see if the solution fits,” explains Chabrak.

Covid-19 Response

As startups and small to medium-sized enterprises (SME) have been seeing their businesses heavily impacted by the measures taken to stop the spread of Covid-19 worldwide, higher education institutions’ innovation and entrepreneurship arms are doing their part to support the ecosystem.

In addition to transitioning its current programmes online and making plans to support its community virtually post-Covid-19, startAD, in association with VentureSouq and Scalable CFO, has launched ‘Runway Grants’ totalling $30,000 that will be awarded to startup alumni in the UAE that have been exceptionally impacted by Covid-19.

SIP is also offering free office space for startups, in addition to intensified connection with mentors and a network of experts to work with founders on spotting opportunities amid the crisis. “Most of the startups are not able to see the opportunity, and think their solution is not working well. We try to help them pivot and find the opportunity,” says Chabrak.

SIP has also launched the Face Shield initiative with Seha and Tawazun, producing face shields for health workers. It also helped to launch a new startup called MetaTouch, which uses patented technology developed by researchers in the university to develop touchless technologies in elevators, in order to limit cross-contamination. It has been installed at Abu Dhabi International Airport and will be rolled out in all government buildings in Abu Dhabi starting in June.

For Taqadam, the programme is helping startups adapt to the new reality by providing mentorship to guide them on how to optimise team communication, focus on lead generation and pivot their business models to cater to market demand. Taqadam ran several hackathons and bootcamps that focused on how to deal with Covid-19.

“Some of the startups have been hit hard, however, some others are coping with the situation,” says Shafi. “Some of our startups are currently launching new services and product lines.”

With access to research and the tools to develop and innovate, universities have the potential to support the most necessary of innovations, but in addition to the incubators and funds, higher education institutions need to ramp up investment in technology transfer offices responsible for creating joint ventures between students and researchers and industry players, in order to promote research commercialisation. Companies and universities need to realise that working in collaborative technology research contributes to the transformation of applied research into technological innovations that can transform society.